On writing as passion and profession: 1927 vs. 2025

+ Figuring out if I still want to do this or not

If you’re reading this newsletter via email: This edition runs longer than usual, so your email service may clip it. Please click on the ‘View entire message’ link if you’re on GMail, or similar links if you're using other email services.

If you’re reading via RSS feed or using the Substack app or other newsletter apps, you’re good. No need to do anything else. 👍🏽

Sabaidi (ສະບາຍດີ; ‘Hello’ in Lao), and welcome to Semi-Online #25.

I’ve been feeling better these past few weeks and enjoying improved mobility, so I’ve gone back to some long-delayed personal stuff, like my MFA thesis turned work-in-progress that I hope to turn into a published book someday. I created a proposal for it, defended that to a three-person panel, and got the green light in September 2019, PCP (Pre-COVID-19 Pandemic). I then went AWOL from the program in 2022 but kept working on it until 2023, when I hit the Pause button.

A peek into history

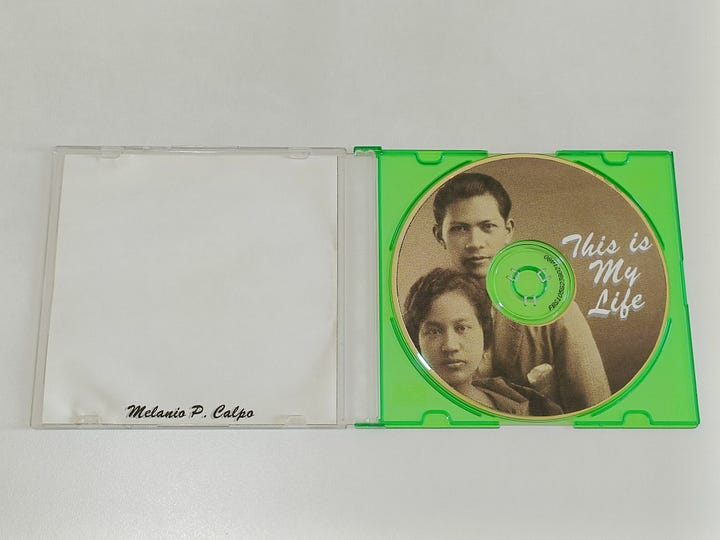

Before my 2019 panel defense, I read several autobiographies relevant to my work and skimmed through some I was just curious about. One of those I skimmed was by Melanio Pascual Calpo, my paternal grandfather. He finished writing This is My Life in 1976, and he made several hardbound and typewritten duplicates for his children. He died in 1989 without adding anything more to it.

Those duplicates deteriorated over time or were completely lost. I think there were only two left by the early 2000s, and they were in pretty bad shape. My older brother was tasked with scanning the typed pages and photographs for posterity before Father Time and bad storage habits took them all away for good. The final product was a CD-ROM, with each chapter rendered in good ol’ HTML frames:

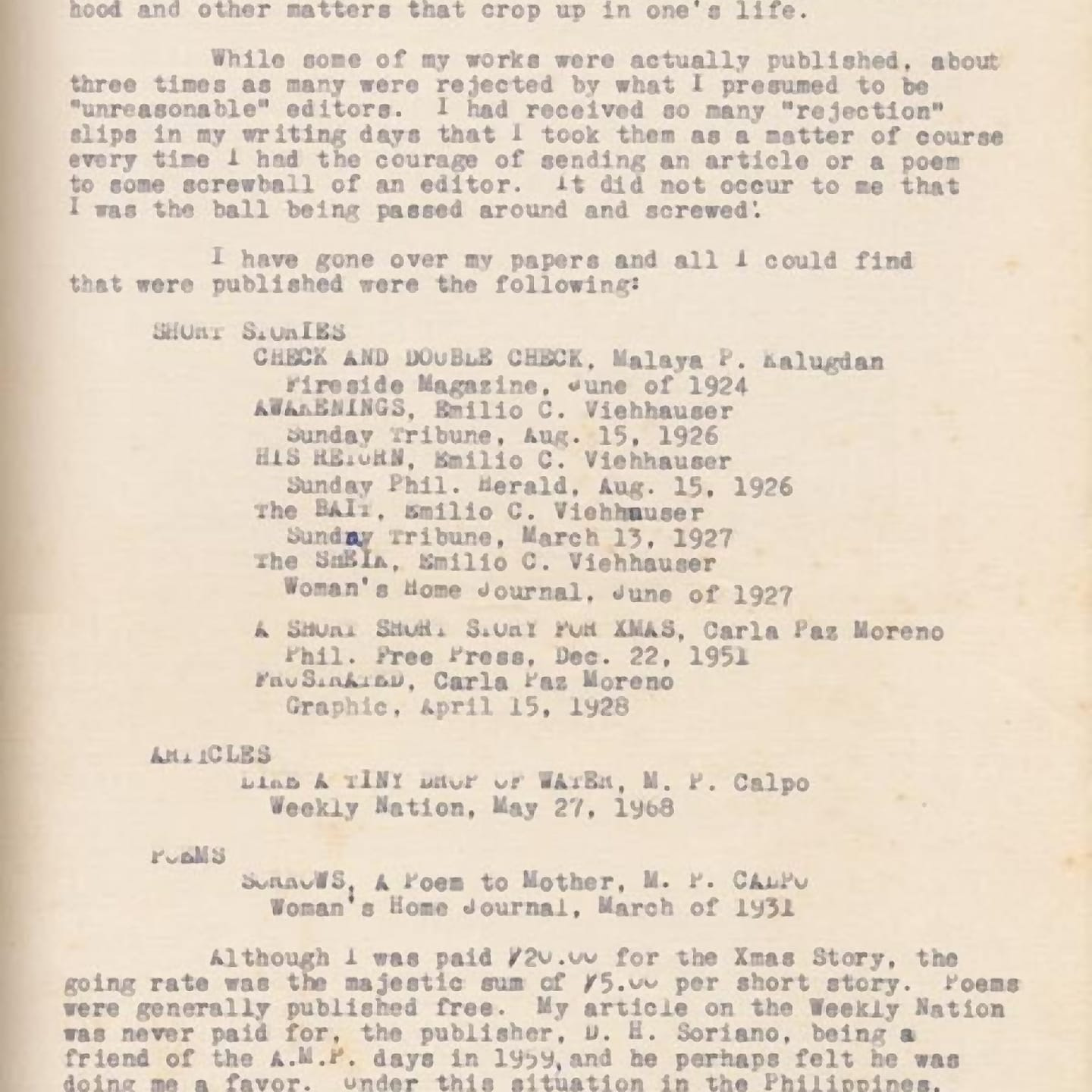

During my autobio-skimming stage, I took those HTML pages and compiled them into a PDF for easier reading on a tablet.1 So you could say that Lolo’s book took on a third form! I’d also focused then on a chapter titled “The Writer”. It was about Lolo’s published short stories and a look at creative writing in the Philippines in an era when it wasn’t considered professional work, or at least it wasn’t described along those lines then. This chapter’s quite short compared to the others and leads me to more questions than answers, plus I still haven’t finished reading the whole book. But I’d say that chapter alone makes the whole book valuable to me.

Lolo never meant for his autobiography to be read by anyone who isn’t an immediate family member or a direct descendant, so I’m keeping its contents private. But some parts of “The Writer” could be considered public record; his stories were printed in publications sold nationwide. So I think it’s OK to show you this screenshot:

I posted this on my personal socials back in 2019, read the rest of the chapter, laughed at what Lolo wrote because goddamn, he was cranky AF and editors are still ‘unreasonable’ today, and moved on to other things.

The 98-year-old ‘surprise’

Let’s skip to May 2025. Atty. Nick Pichay, my former professor for playwriting techniques, had delivered this year’s Paz Latorena Memorial Lecture at the University of Sto. Tomas (UST), the oldest university in the Philippines and Asia at 414 years old. I’m happy he was chosen for it, but there was also a tiny bell ringing in my head that wasn’t SSCD-related tinnitus. Paz Latorena. PAZ. L A T O R E N A. I KNOW THIS NAME. I’ve seen it somewhere before, and not from my Literary History class and MFA comprehensive exams. But I just couldn’t remember, so I had to let it go.

A week ago, I went through Lolo Melanio's autobiography again for an unrelated reason. I opened This is My Life, went back to “The Writer” chapter, and found this at the end:

There she is! Paz M. Latorena, “one of the notable writers of the first generation of Filipino English writers,” was sitting on the chair right beside my grandfather, who’s standing at extreme left. The UST’s official school publication The Varsitarian called her a literary doyenne, while Rappler described her as:

…a distinguished figure in Philippine literature in English. Latorena was a professor of English and literature at UST’s former Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, where she influenced a generation of literary figures, including National Artist F. Sionil José, Eugenia Duran Apostol, Genoveva Edroza Matute, Zenaida Amador, Ophelia Alcantara Dimalanta, and Alice Colet-Villadolid.

But wait, there’s more! This photo and the short accompanying writeup announced the formation of the Philippine Writers’ Association (PWA). It aimed to gather the country's best literary writers and ‘professionalize’ their production and other endeavors. Membership was based partly on their personal and professional ties; Lolo knew many of them from his former jobs, past residences, and existing friendships.

Given the scant info available today about the PWA—there’s a brief mention of it on the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) website thanks to poet Ricardo de Ungria, but not much else—it’s obvious that this effort didn’t last. But its extreme short-livedness is just fucking hilarious to me:

We were so grandiose in our objectives that the whole thing amounted to an improbability, i.e.:

To upgrade the technique of writing by going into Grammar school again;

To conduct seminars on good stories, starting from the idea of the “plot”, the “development” and the “denouement”;

To establish a Board of Censors among ourselves;

To make our efforts felt by all publishers, etc., etc., etc.

Thirty two individuals of independent minds, naturally, could not possibly agree on anything. The matter of the “Grammar School” and “Censorship” hurt the feelings of many. The “Seminars” were taboo because no one wanted to reveal a trade secret. All realized that we were simply at the mercy of the Editors who usually did not even read the whole “story” and so our dreams went pffft… We did not even reach the election stage!

Yep. Massive egos and secrets. That tracks. 🤷🏽

For those curious about the other names in the January 1927 Philippines Free Press article, some of whom later became trailblazers in Philippine letters, law, medicine, etc.:

Mario Bengson, Alfredo Densico, Domingo H. Soriano, Oscar Juco, Jose Villa (could be José García Villa), J. Villa Panganiban, Pablo T. Anido, Isidro Retizos, Vicente Perez, Jose Albornoz, Rosendo A. Medina, Ciriaco Buen, B. Chavarria, Pablo Menez, Dominador Manas, Rafael Ituralde, Antonio Senatin, Mercedes L. Grau, Salud Chavarria, Rosa Franco, Loreto Paras, Salvador Pena, Rizal G. Adorable, José V. Clariño, Rizal G. de Peralta, Tomas O. Magno, Jose M. Hernandez, Augusto Catanghal, A.B. Rotor, Aurelio Zurbano.

Then and now

The more, the manyer

From a big-picture point of view, the PWA is a blip in Lolo’s and his peers’ lifetimes and long careers. Many more writers’ groups have formed in the decades since—with either definitive intentions and wide coverage (like Unyon ng mga Manunulat sa Pilipinas or UMPIL) or smaller, genre-based, and/or regional memberships—and have varying degrees of success and longevity. The same goes for publications, workshops, grants and fellowships, etc. here in the Philippines and for Filipinos abroad.

I don’t have sufficient space or knowledge to get deep into Philippine literary history here, especially since I focused on creative nonfiction in grad school and Lolo was into short fiction, so we’re on two very different sides of a very long story. But I can say that modern Philippine creative writing is thriving (despite, well, everything) and gives its people—veterans and newcomers, traditionalists and independents, hobbyists and careerists—plenty of options. Our writers write in multiple languages, not just English, nor does English remain the sole arbiter of ‘quality’. And Lolo would probably be astounded at the publishing and distribution options and technologies we have today that he never did or even thought possible. From zines to worldwide bestsellers, there are multiple routes to publishing now and you can choose which is best for you.

The commercial side of writing has learned to band together, too. I was a member of the Freelance Writers’ Guild of the Philippines (FWGP) in its first version in the early ‘10s. I’ve yet to rejoin the current version, but it has a healthy membership and projects in the pipeline. Bills are also being made to protect us, but there’s nothing concrete yet. Again, that’s better than having nothing.

…But it’s still complicated

Some aspects remain unchanged from 1927 onward, though. A sample:

Literary preservation has been spotty at best and frustrating at all times. Even my own grandfather didn’t keep all of his papers or clippings! Nor does he have a literary estate.2

Writers still refer to short-term assignments as ‘raket’, and it truly grinds my gears. Sometimes, the disrespect for writing as a profession comes from our own ranks.

The public depends on writers for information and entertainment, but they utterly refuse to pay us for our work, much less provide a decent wage or regularization or give the smallest bit of respect. Worse, they insist that we’re ‘just’ writers and that anyone can write—or they replace us completely with AI! 🤬

Another money bugbear: We can’t support ourselves solely through writing. To make it month to month, we need a main job + multiple side jobs + a partner, spouse, or parent with a much higher monthly income + connections to the padrinos and ‘gatekeepers’ who absolutely hate being called gatekeepers even if they 100% are. Subtle ring-kissing and ‘gratefulness’ are musts here in the Philippines, and I’ve always hated it.

Both literary and commercial writing function on hierarchy, control, and secrecy. Some old-school writers still consider a long list of publications, national writing workshops, grants, research, etc. the only acceptable marks of a writer’s legitimacy. Our writers seldom talk about crossing trade lines (no matter how common it is) because it’s considered shameful for artists to need money, or audacious for those with (some) money to even dream of making art. Or we still can’t teach other writers where and how to look for work and how much to charge and pay in taxes because they could poach our clients at any time. So Filipino writers stick to our cliquish literary and freelancer barkadas, and maybe keep some vital information to ourselves at writing and publishing workshops so we still have the perceived upper hand. And the traditional publishing folks also still look at independent writers with unmistakable disdain. (Don’t lie; we know you do. There’s a recent pivot to celebrating self-publishers and including them in the 2025 Frankfurt Book Fair contingent, but I still remember what you really thought of them before their books started outselling yours.)

As for the other PWA conditions? No to censorship, especially after Martial Law. Still no to Grammar school; oh, the older and/or more experienced writers will surely say “How dare you!” 💀 And “Our efforts felt by all publishers”? That depends on their bosses, budgets, and received backlash. And that’s another long conversation 😣

Bylines and career paths, decades apart

I used to be so annoyed whenever my paternal relatives learned I write because they always had this standard response: “Lolo was a writer, too! You should read his book!” They seemingly told me that he already did everything worth doing, and I was just following in his footsteps and wasn’t good for much else.

Now that I’ve actually read parts of it… OK, fine, I should’ve read it earlier 🙃 And I was walking the same path as him, somewhat. He and I wrote for the same publication 87 years apart! I too wrote for the Philippines Graphic,3 and was in talks for a marketing project with the Philippines Free Press until it suddenly shut down in 2011.

(Re)learning that my grandfather was part of the PWA in 1927 is big for me for another reason. I’m the only one in my father’s side of the family who still/sometimes writes for a living, and I don’t know anyone from my mother’s side who’s ever done it. Some write as a hobby, some worked as writers before but have moved on to other industries, and at least one niece wanted to take it up (and had asked me for advice). Knowing there was one person who did it before me, no matter how inconsistent or occasional, and did it the hard way reminds me that I haven’t quite lost my marbles.

It’s also amazing to me that Lolo Melanio rolled with people who would become Philippine literature heavyweights. If he kept writing his short stories or was consistent with his output, I truly think he could’ve made a name for himself, too. I have to finish reading This is My Life to find out why his writing career went hot and cold throughout his lifetime, but at least I now know na may pinagmanahan talaga ako 🤭

He died when I was still quite young, and I don’t remember him at all. There are pictures to prove we’ve met but I have no personal stories of him to tell, unlike my older siblings who knew him better. So This is My Life provides plenty of answers, but writing career-wise, I have more questions to ask if he were still here, like:

Why was your creative output on and off? I know you lived through two world wars (and several foreign invasions), upheavals of all kinds, creating and raising 14 children (and burying some of them), Martial Law, etc. I know you were busy living your life, man. But… why?

How did you deal with your peers’ success post-1927? We all know we shouldn’t compare or list achievements, but we all do it in private. How’d you handle internal pressure, envy, and maybe not having the same options and security (financial, housing, employment, familial, etc.) as they did?

What other stories did you want to write, but never got the chance to?

Is there anyone among your children who could’ve taken up writing as a profession, too?

The dream could stay just that, and that's alright

Looking back at “The Writer” also made me reassess my own future as a creative and commercial writer.

I used to dream of helming a print publication, and then an online publication. Then both industries went bust. I used to have a solid client list and plenty of time and energy to write for work plus myself. Then disability and depression and displacement and COVID-19 and everything else came at me hard. I’m looking at the industries I work(ed) in and I’m trying to find ways back. But the landscapes have changed so much or have been massively walloped by AI that it’s like I’m starting all over again—and left holding way more cards than everyone else. We’re always told to strive for success and greatness, to write every day and do all sorts of things to attract and keep a readership. But what’s success for me now aside from being debt-free and not in a coffin? I’m trying to write my stories and mind my own business and get to the First Draft stage. But there are too many writers and critics and randoms demanding fair play but also throw out ‘rich kid’ and ‘Imperial Manila’ and ‘Oppression Olympics’ at people and stories they don’t like or aren’t even about them or remotely connected to them in any way. Oh, and no one’s getting paid fairly, and platforms like Substack and gateways like Stripe still think Global South writers can stay unpaid because the poors can’t ever have money 🖕🏽

So… what now?

Maybe following my grandfather's example—taking his damn sweet time and limiting access to his final work only to those he loved—is just fine. Maybe it’s time to learn new skills and move to other industries. Life’s short; cut your losses and move on, right? There’s no shame in tapping out of the dream when you’ve outgrown it or it has outgrown you; or in pursuing other, more attainable dreams.

Or maybe I can still chip away at both sides whenever I can. It took Lolo Melanio until his 70s and retirement to get to a finished manuscript. One and done is fine, too.

Yeah, I’ll get back to you.

Semi-Online is a free newsletter and accepts tips via Ko-fi and Buy Me a Coffee.

As of 2025, Substack and Stripe, its only built-in payment gateway, still don’t allow Filipino creators to offer paid subscriptions. Nor does it seem like Substack will use other (and more widely accepted) payment gateways.

You can pledge a future paid subscription in case Substack changes its mind or gives in to global pressure for fair earning opportunities for ALL Substack creators. Until then, you won’t be charged.

Semi-Online is also listed on three Substack directories: Stack Natin, Periphery (formerly Asian Writers’ Collective), and SmallStack. Check them out and discover excellent longform writing from creators based in the Philippines, the Filipino diaspora, and Asians worldwide + Substacks with fewer than 1,000 subscribers!

If you have any feedback, suggestions, and/or complaints about this newsletter, please comment below, email me, or talk to me on Mastodon.

Don't ask me how I did it; I've long forgotten 🤭 I use Ubuntu, so my best guess would be I pulled the content from the default Nautilus file manager app, then ran compile commands through PDFtk and Terminal.

If anyone has any copies of Melanio P. Calpo’s short stories mentioned above, or access to the archives of the publications he mentioned, please let me know. I (and maybe some literature-loving family members) would love to read his stories.

The Graphic is still alive in 2025, but its administration fired my friends and overhauled its Editorial team in July 2020, so I probably won’t write for it again. But I wonder if it has a well-maintained archive…

Though this is sad to learn, thank you for sharing the old and modern realities and that not much has changed for Filipino writers living in the Philippines. I hope you find the lost literary gems of your Lolo Melanio.

I love that your lolo wrote about his life, and especially love the screenshot with his thoughts on rejection. I can totally relate!